Hair restoration has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past century, evolving from experimental procedures to sophisticated surgical techniques. What began as crude grafting attempts has developed into one of medicine’s most refined microsurgical specialties, offering patients natural-looking results that were once thought impossible.

Today’s hair transplant patients benefit from decades of innovation and refinement. However, this level of sophistication didn’t happen overnight. The journey from early “plug” procedures to modern follicular unit techniques represents a fascinating evolution of surgical skill, patient demand, and technological advancement.

Understanding this historical progression is valuable for anyone considering hair restoration. It helps patients recognize modern techniques, avoid outdated approaches, and set appropriate expectations based on proven scientific principles.

Key points:

- 1897 – Dr. Menahem Hodara performed the first documented hair transplant experiment in Istanbul

- 1939 – – Dr. Shoji Okuda develops the first successful punch graft technique in Japan

- 1952 – Dr. Norman Orentreich performs the first transplant for male pattern baldness in New York

- 1959 – Donor dominance principle established, providing a scientific foundation for permanent results

- 1960s-1980s – “Hair plug” era produces artificial results but proves hair transplantation viable

- 1984 – Mini-grafting and micro-grafting techniques create a more natural appearance

- 1992 – Drs. Yung Chul Choi and Jung Chul Kim developed Direct Hair Implantation (DHI) using the Choi Implanter Pen

- 1995 – Drs. Robert Bernstein and William Rassman introduced Follicular Unit Transplantation (FUT)

- 2002 – Follicular Unit Extraction (FUE) formally introduced by Drs. Rassman and Bernstein

- 2010s – Sapphire FUE technology emerged for minimal scarring

- 2010s – Long-Hair FUE developed using Dr. Sanusi Umar’s Zeus U-graft machine, eliminating need for shaving

- 2011 – ARTAS Robotic Hair Transplant System introduced

Ancient Hair Restoration Attempts

Hair restoration attempts date back to ancient civilizations, with Egyptians using elaborate wigs and Greeks developing herbal scalp treatments around 400 BC.

Ancient civilizations approached hair loss with the tools and knowledge available to them. Egyptian culture placed enormous importance on appearance, leading to the development of sophisticated wig-making techniques using human hair, sheep wool, and plant fibers. These weren’t merely cosmetic choices; baldness was often associated with illness or social status.

Greek physicians, including Hippocrates, developed various herbal treatments and scalp stimulation techniques. While these methods couldn’t regenerate lost hair, they demonstrated early understanding that hair loss could potentially be addressed through intervention.

Indian Ayurvedic medicine contributed oils, herbs, and massage techniques that share surprising similarities with modern scalp stimulation therapies. These ancient approaches, while limited in effectiveness, established the foundation for viewing hair loss as a treatable condition.

The transition from concealment to surgical intervention began in the late 19th century, as medical understanding of skin grafting and wound healing advanced.

The First Documented Hair Transplant Experiment Happened in Istanbul in 1897

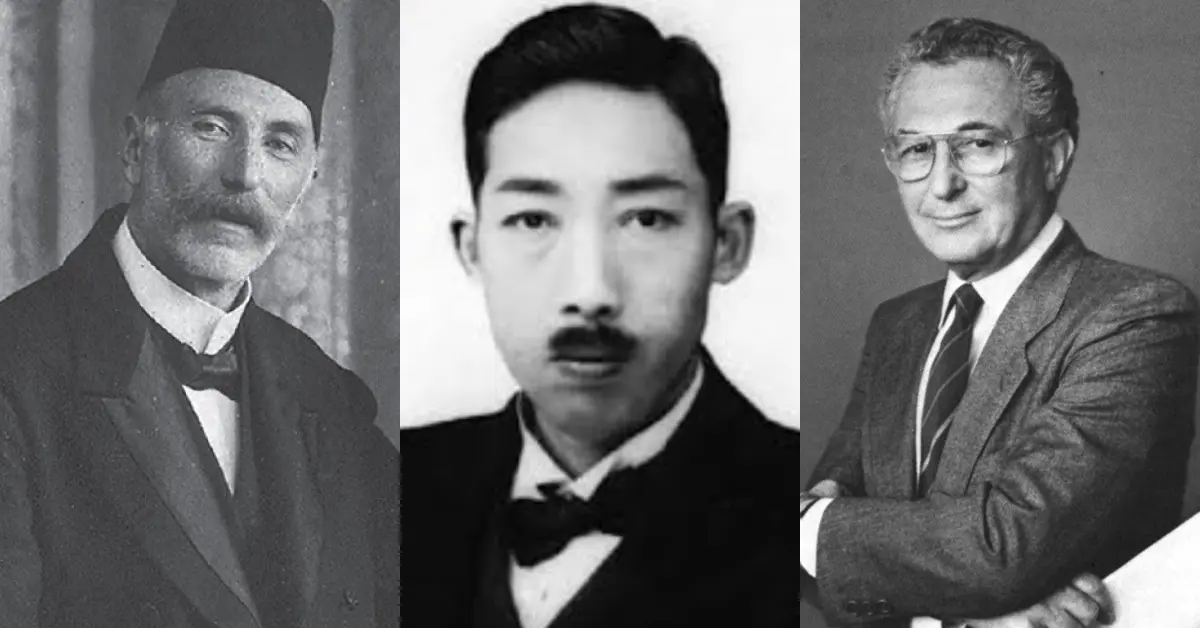

Dr. Menahem Hodara performed the first documented hair implantation experiment in 1897 in Istanbul, treating favus scars by implanting hair pieces into scarified incisions.

The earliest recorded attempt at surgical hair restoration was conducted by Dr. Menahem Hodara (1869-1926), a Sephardic-Turkish dermatologist and founding member and first president of the Turkish Society for Dermatology and Venereology, working at the Central Marine Hospital in Istanbul.

On March 26, 1897, Dr. Hodara shared his important experiment with the Imperial Society of Medicine in Istanbul. This marked the first recorded “hair transplant” procedure in medical history.

Dr. Hodara’s experiment focused on treating favus, a serious fungal infection of the scalp. Favus caused severe scarring and permanent hair loss, leading to visible bald patches that disfigured patients.

Dr. Menahem Hodara’s Early Technique

Dr. Menahem Hodara developed a hair transplant method that was basic compared to today’s techniques, but it was groundbreaking at the time.

He took hair from healthy parts of patients’ scalps and cut these pieces to lengths between 1 and 4 millimeters. Then, he made several shallow cuts on the scarred areas and placed the hair pieces directly into the wounds.

The technique resembled “hair planting” more than modern than follicular transplantation. Dr. Hodara was not moving living hair follicles with roots; instead, he inserted cut hair shafts into treated skin. After covering these areas with dessings, he waited four weeks before checking the results.

Results and Limitations of Dr. Menahem Hodara’s Experiment

Dr. Hodara had mixed but significant results. When removing the dressings after four weeks, most of the implanted hairs had fallen out. However, some hairs remained to provide coverage over the treated areas. After 3-4 months, some of the surviving hairs became pigmented and strong, while others stayed thin and colorless.

Microscopic exams showed that the remaining hairs had created new bulbs at their base, indicating some real hair growth had happened. Although the success rate was low and the method was basic, Dr. Hodara proved that hair implantation could work in theory.

International Reception and Controversy

Dr. Hodara’s experiment received a lot of attention from the media worldwide, with headlines like “Baldness conquered at last” and “No more bald heads.” However, many doctors were not as convinced and were more skeptical about the results.

Several dermatologists, including Dr. Havas at the 1914 Congress of the German Society of Dermatology, criticized Hodara’s method, saying it was not accurate and that successful hair growth was just a fantasy. In 1906, Dr. Kapp reported that he did not see any success when he tried to replicate Dr. Hodara’s technique.

Dr. Hodara strongly defended his work, saying his results were accurate and backed up by tissue study evidence. Dr. Paul Unna, a well-respected editor of Dermatologische Wochenschrift, supported Hodara’s claims. He said he examined Hodara’s samples and found the data to be “absolutely correct.”

Historical Significance of Dr. Menahem Hodara’s Experiment

In 1897, Hodara conducted an experiment that, while different from today’s hair transplant methods, laid important groundwork. He was the first to show that transplanted hair could grow in a new location. His work also pointed out the difficulties of hair restoration surgery and the need for better techniques.

It is notable that the first hair transplant surgery was performed in Istanbul by Dr. Hodara, the inaugural president of the Turkish Society for Dermatology and Venereology. Since that time, Istanbul has been recognized as the “hair transplant capital of the world”, a full circle moment.

When did modern hair restoration first begin? (1930s-1950s)

The foundation of modern hair transplantation emerged from Japanese medical innovation in the 1930s and 1940s, followed by crucial American discoveries that established the scientific principles still used today.

Who invented hair transplant surgery? (1939-1943)

Dr. Shoji Okuda invented modern hair transplant surgery in 1939 in Japan, using punch grafts to restore hair in injured scalp areas.

Working with patients suffering from scarring alopecia caused by favus (a fungal infection), Dr. Okuda developed a punch graft technique using small circular tools ranging from 1,5-5 mm in diameter. His method involved carefully removing hair-bearing tissue from healthy scalp areas and transplanting it to scarred regions.

The significance of Okuda’s work cannot be overstated. He proved that transplanted hair follicles could survive and continue growing in new locations. This fundamental principle became the foundation for all future hair restoration surgery.

Dr. Hajime Tamura advanced Dr. Okuda’s techniques by recognizing that smaller grafts produced superior results. Tamura began subdividing larger spindle-shaped grafts into individual hair follicles, essentially pioneering what would later become known as follicular unit transplantation. His insight that smaller grafts created more natural results was decades ahead of its time.

Unfortunately, World War II limited the dissemination of these Japanese innovations, and their groundbreaking work remained largely unknown to the Western medical community for several decades.

American Innovation (1952-1959)

The modern era of hair transplantation began in 1952 when New York dermatologist Dr. Norman Orentreich performed the first hair transplant specifically for male pattern baldness with 4mm punch “plug” grafts. Orentreich’s contribution extended beyond the surgical technique itself. His most important discovery was the principle of “donor dominance.”

Donor dominance is the principle where hair follicles from the back and sides of the scalp maintain their resistance to balding even when transplanted to bald areas.

Through careful observation of his transplant patients, Orentreich discovered that hair follicles transplanted from the permanent fringe areas (back and sides of the scalp) retained their original characteristics. These transplanted hairs continued growing normally in balding areas, maintaining their resistance to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and androgenetic alopecia.

This discovery provided the scientific foundation for all future hair transplantation. Published in 1959, Orentreich’s work on donor dominance established that hair restoration surgery could provide permanent, predictable results.

Hair Plugs (1960s-1980s)

Hair plugs were large 4mm grafts that created an artificial appearance because they didn’t match natural hair growth patterns.

The large grafts produced clusters of thick hair separated by areas of normal balding, resulting in a characteristic “polka-dot” pattern. Patients often described the results as resembling doll hair. The unnatural appearance was immediately recognizable and often became a source of social embarrassment.

Despite these cosmetic limitations, many patients accepted plug transplants because they represented the only surgical option available. For men experiencing significant hair loss, even artificial-looking hair was preferable to progressive balding.

During this era, some surgeons experimented with alternative techniques, including scalp flaps (relocating large sections of hair-bearing scalp) and scalp reductions (surgical removal of bald areas). However, these procedures often resulted in unnatural hair direction, visible scarring, and distorted scalp anatomy.

The aesthetic problems of the plug era created a significant challenge for the field of hair restoration. Patient dissatisfaction and social stigma threatened to undermine the credibility of surgical hair restoration entirely.

Mini and micro grafts (1980s-1990s)

Hair transplants began looking natural in 1984 with the introduction of mini-grafts and micro-grafts, which used smaller, more refined pieces cut from donor strips.

The 1980s marked a turning point in hair transplant surgery as practitioners recognized the need for more natural-appearing results. In 1984, two critical developments revolutionized the field simultaneously.

The first was the introduction of the “mini-grafting” technique. Instead of using punch tools to extract round grafts, surgeons began harvesting thin strips of scalp from the donor area and carefully dissecting them into smaller units.

More importantly, Dr. John Headington published groundbreaking research in Archives of Dermatology that scientifically described follicular units as distinct anatomical structures containing 1-4 naturally grouped follicles. Headington’s discovery of these natural hair groupings provided the crucial scientific foundation that would later make follicular unit transplantation (FUT) possible in the 1990s.

The mini-graft approach utilized a gradient strategy for optimal aesthetics. Larger mini-grafts (containing 3-8 hairs) were placed in central areas to provide density, while smaller micro-grafts (containing 1-2 hairs) created soft, natural-appearing hairlines. This technique represented a significant improvement over the obvious plug appearance of earlier procedures.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, surgeons refined their dissection techniques and began performing “mega-sessions” involving thousands of grafts, allowing for more comprehensive coverage in fewer procedures.

However, the mini-graft era still had limitations. Despite Headington’s anatomical discoveries, graft sizes remained somewhat arbitrary rather than consistently following the natural follicular unit structures he had identified. Mini-grafts that were too large might still appear slightly artificial, while areas with only micro-grafts could appear thin. This disconnect between Headington’s scientific understanding and the continued use of arbitrarily sized grafts would soon be resolved by surgeons who fully embraced his anatomical principles.

Follicular Unit Transplantation (FUT) (1995 onwards)

FUT (Follicular Unit Transplantation) removes a strip of scalp and dissects it into natural 1-4 hair groupings under microscopes for natural results.

The most significant advancement since Orentreich’s original work came with the recognition and utilization of follicular units, the naturally occurring groups of 1-4 hair follicles found in normal scalp anatomy.

Dr. Bobby Limmer (1988-1994) developed stereo-microscopic dissection techniques essential to FUT, published as “Elliptical donor stereoscopically assisted micrografting” in 1994. Dr. Robert Bernstein and Dr. William Rassman built upon Dr. Limmer’s foundational work.

Dr. Robert Bernstein and Dr. William Rassman introduced Follicular Unit Transplantation (FUT) in 1995, building on concepts pioneered by Dr. Bobby Limmer. This technique represented a fundamental shift from arbitrarily sized grafts to anatomically correct transplantation.

The FUT procedure involves surgical removal of a strip of hair-bearing scalp from the donor area, typically from the mid-occipital region. The harvested strip is then meticulously dissected under stereoscopic magnification to isolate individual follicular units while preserving their natural architecture.

This microscopic dissection requires exceptional skill and precision. Each follicular unit must be carefully separated while maintaining the integrity of the surrounding perifollicular tissue. The resulting grafts contain 1-4 hair follicles arranged in their natural configuration.

The aesthetic results of FUT were revolutionary. By transplanting hair in its natural groupings, surgeons could recreate normal hair density and growth patterns. The artificial appearance of previous techniques was eliminated, replaced by results that were virtually indistinguishable from natural hair growth.

Patient satisfaction with FUT drove rapid adoption throughout the hair restoration community. By 2000, FUT had become the gold standard for surgical hair restoration worldwide. The technique enabled larger sessions while maintaining graft quality, making it possible to achieve significant coverage in fewer procedures.

FUT does result in a linear scar in the donor area where the strip is harvested. However, advanced closure techniques, particularly the trichophytic closure, help minimize scar visibility. Most patients consider this trade-off acceptable given the superior aesthetic results achieved.

Follicular Unit Extraction or Excision (FUE) (2000s)

The early 2000s brought the next major evolution in hair transplant technique, focusing on eliminating the linear scar associated with strip harvesting while maintaining the quality results achieved with follicular unit transplantation.

FUE extracts individual follicular units using 0.8-1.0mm punches, leaving only tiny scattered scars instead of a linear scar.

Follicular Unit Extraction (FUE) was formally introduced in 2002 by Drs. William Rassman and Robert Bernstein, though similar concepts had been explored by Dr. Ray Woods in Australia during the late 1990s.

FUE represented a fundamental change in harvesting methodology while maintaining the follicular unit principles established by FUT.

The FUE technique uses small circular punches, typically 0.8-1.0mm in diameter, to score around individual follicular units in the donor area. Each unit is then carefully extracted using specialized forceps. The resulting micro-wounds heal independently without requiring sutures, leaving only tiny scattered scars rather than a linear incision.

The primary advantage of FUE is the absence of a linear donor scar, allowing patients to wear shorter hairstyles without visible evidence of surgery. This “scarless” approach appealed to many patients, particularly those who preferred buzz cuts or very short hair.

However, FUE presented significant technical challenges. The procedure was extremely labor-intensive and required development of new surgical skills. Initial graft survival rates were often lower than FUT due to increased manipulation and the learning curve associated with the technique.

Dr. Jim Harris introduced the SAFE System in 2005, significantly improving FUE outcomes. This two-step approach used a sharp punch to score the superficial skin followed by a blunt punch to dissect around the follicle, reducing the risk of graft transection.

The late 2000s saw the development of motorized FUE devices, including rotary and oscillating handpieces that increased extraction speed and consistency. Automated systems like NeoGraft and SmartGraft further refined the process by incorporating suction assistance and standardized protocols.

By the 2010s, FUE had gained widespread acceptance and often rivaled FUT in popularity. Experienced surgeons could achieve graft survival rates and aesthetic outcomes comparable to strip harvesting, while offering patients the advantage of minimal scarring.

Direct Hair Implantation (DHI) (2000s onwards)

DHI uses specialized implanter pens to place grafts directly without pre-made incisions, offering precise control over angle and depth.

Direct Hair Implantation represents an evolution in graft placement methodology that builds upon the FUE extraction method. DHI combines FUE harvesting with advanced implantation techniques using the Choi implanter pen, a specialized surgical instrument that allows surgeons to make an incision and implant a single hair follicle simultaneously.

The Choi pen was developed by Dr. Yung Chul Choi and Dr. Jung Chul Kim in Korea and was first manufactured by Akio Kakinuma in 1992. In their groundbreaking paper “Single Hair Transplantation Using the Choi Hair Transplanter,” the pair invented the Choi pen and developed the modern DHI hair transplant technique for the first time to achieve single hair follicle transplantation. They successfully reconstructed hairlines, eyebrows, facial hair, and burn scars.

The Choi pen was inspired by a single implanter pen developed in the 1960s by medical assistant Chung Ki Paek, which was used to perform eyebrow reconstructions. The device consists of a loading chamber, plunger mechanism, and needle tip ranging from 0.8-1.0mm in diameter.

The Choi pen allows surgeons to control three critical aspects of follicle placement: depth, angle, and direction of implanted grafts. The surgeon loads a follicular unit into the device and then creates the recipient site while inserting the graft in a single motion, providing precise control over placement.

Today, DHI procedures predominantly use FUE extraction methods to harvest follicular units, which are then implanted using the specialized pens. This combination of FUE harvesting with precise implantation has made DHI a popular choice for achieving natural-looking results with minimal tissue trauma.

Sapphire FUE Technology (2010s onwards)

The Sapphire FUE technique builds on the regular FUE method by using sapphire blades to make incisions for implantation instead of regular steel blades. This innovation focuses specifically on the incision-making phase of the procedure, not the extraction process.

A sapphire blade is a surgical instrument made of a single synthetic sapphire crystal, cut at angles to work as a scalpel. The angles can be cut at 30° or 60°, with blades ranging in size from 0.15mm to 0.35mm. Sapphire blades used during Sapphire FUE procedures typically come in 30° and 60° tip angles.

The key advantage lies in material properties. Sapphire blades have a hardness level of 9 on the Mohs scale, compared to steel, which has a hardness rating of 5. This makes sapphire blades significantly more durable compared to steel blades, which can dull very quickly during lengthy procedures.

Sapphire blades allow surgeons to create thinner and more densely packed incisions for optimal hair transplant results. The precision of these ultra-thin blades enables better coverage and more natural-appearing density.

The thinness of sapphire blades results in minimal scarring, trauma, and swelling from the surgery compared to steel scalpels. Research has shown that 30° sapphire blades cause the least amount of damage to scalp tissue compared to other blade types, contributing to faster healing and improved patient comfort.

Robotic Hair Transplant (2010s onwards)

Hair transplant robots like ARTAS use AI-guided optical systems and robotic arms to harvest grafts with micron-level precision and consistent accuracy.

The integration of robotic technology represents the current frontier in hair transplant innovation. The ARTAS Robotic Hair Transplant System, introduced in 2011 by Restoration Robotics, incorporates artificial intelligence and robotic precision to assist surgeons in FUE procedures.

The ARTAS system utilizes high-resolution stereoscopic imaging and AI algorithms to identify optimal follicular units for extraction. A computer-controlled robotic arm then positions dual-punch mechanisms with micron-level accuracy to harvest grafts with consistent precision throughout the procedure.

The 2017 ARTAS 9x system introduced significant enhancements, including faster punch cycling, advanced visual recognition capabilities, automated scar detection, and smaller 20-gauge needle punches for reduced tissue trauma. These improvements increased both efficiency and patient comfort.

Current ARTAS iX models can perform both graft harvesting and recipient site creation, with some functionality for automated graft placement. The system can analyze donor areas and harvest grafts in uniformly distributed patterns to avoid over-harvesting any single region.

While robotic technology offers unprecedented precision and consistency, these systems remain tools that enhance rather than replace a surgeon’s expertise. Human judgment continues to be essential for treatment planning, artistic design, and final graft placement to achieve optimal aesthetic outcomes.

Long-Hair FUE (2010s onwards)

Long-Hair FUE was developed to eliminate any visible appearance of surgery, allowing patients to undergo hair transplantation without shaving either the donor or recipient areas.

Long-Hair FUE represents a revolutionary advancement that completely eliminates the need for shaving during hair transplant procedures. This technique was developed using the Zeus U-graft machine, developed by Dr. Sanusi Umar, which allows for the harvesting and transplantation of hair at its natural length.

The Zeus graft machine enables surgeons to extract donor hair follicles while maintaining their full length, rather than cutting them short as in traditional FUE methods. These long donor hairs are then implanted directly into the recipient area without any shaving of the existing hair in that region.

The technique provides complete surgical discretion; there is no visible appearance that surgery has taken place. Patients can return to their normal activities immediately without anyone detecting that they have undergone a hair transplant procedure.

The transplanted long hairs remain visible for a few weeks before naturally shedding, after which new hair growth begins within a few months following the normal hair growth cycle.

This no-shave approach has made hair transplantation accessible to patients who previously avoided the procedure due to concerns about visible evidence of surgery. The technique is particularly valuable for professionals, public figures, or anyone who cannot afford social or professional downtime associated with traditional hair transplant methods.

Long-Hair FUE represents the ultimate in surgical discretion and advancement, allowing patients to undergo hair restoration while maintaining their existing appearance throughout the recovery process.

The Future of Hair Restoration

Current trends suggest several directions for future development in hair restoration surgery. Robotic technology will likely become more sophisticated, potentially handling larger portions of procedures with greater precision.

Stem cell and regenerative medicine research may eventually provide alternatives to traditional donor harvesting.

Artificial intelligence applications beyond robotics could optimize treatment planning, predict outcomes, and enhance surgical decision-making. Advanced imaging and simulation technologies may improve patient education and expectation management.

With advancements in the pharmaceutical field, hair loss may not need to be treated with surgical interventions at all, and can be permanently managed with medications.

References:

- INUI, S. and ITAMI, S. (2009), Dr Shoji Okuda (1886–1962): The great pioneer of punch graft hair transplantation. The Journal of Dermatology, 36: 561-562. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00704.x

- Jimenez, F. and Shiell, R.C. (2015), The Okuda Papers: an extraordinary – but unfortunately unrecognized – piece of work that could have changed the history of hair transplantation. Exp Dermatol, 24: 185-186. https://doi.org/10.1111/exd.12628

- Unger, Walter P.1. The History of Hair Transplantation. Dermatologic Surgery 26(3):p 181-189, March 2000. | DOI: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.00503.x

- Moeckel, Camille BA*; Chacharidakis, Georgios MD†; Balasis, Stavros MD‡; Queen, Dawn MD§; Avram, Marc R. MD||; Panagiotopoulou, Gianna MD¶. From Scalp Flaps to Follicular Units: A Historical Perspective on Hair Transplantation Techniques. Dermatologic Surgery ():10.1097/DSS.0000000000004581, February 26, 2025. | DOI: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000004581

- Tekiner H, Karamanou M. The forgotten hair transplantation experiment (1897) of Dr. Menahem Hodara (1869-1926). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016 May-Jun;82(3):352-5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.179089. PMID: 27088955.

- Chauhan K, Tandon M, Kumar A, Taneja N, Hamid SAT. A comprehensive review of evolution of advanced follicular unit excision systems. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2025 Apr-Jun;18(2):69-77. doi: 10.25259/JCAS_4_2024. Epub 2024 Dec 18. PMID: 40212421; PMCID: PMC11980712.

- Hair Transplant Forum International September 2000, 10 (5) 151; DOI: https://doi.org/10.33589/10.5.151

- Choi, Yung & Kim, Jung. (1992). Single Hair Transplantation Using the Choi Hair Transplanter. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 18. 945-8. 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb02765.x.